Life after isolation

Years after their release, formerly incarcerated people live with the long-term mental health effects of solitary confinement

Warren

Every time he arrives home, Warren washes his hands seven times. He is not scared of contracting COVID-19, but he can still feel the filth from the years he spent in solitary confinement.

He was only allowed a 10-minute shower once a week. Three years later, his hygiene practices became excessive hygiene practices and he self-identifies as a germaphobe.

But the negative impacts of solitary confinement extend far beyond hygiene habits. Research has shown that prolonged isolation can lead to panic attacks, anxiety, depression, psychosis, social withdrawal, outbursts of violence, and even suicide, which may persist years after release.

In New York State, nearly 9% of incarcerated individuals are still subjected to solitary confinement every other day. These individuals may endure months or even years of complete isolation, stripped of any meaningful social interaction.

Five

Five was having a good day until his friend disappeared. The fly he had been talking to was nowhere to be seen in his 6’ x 9’ cell. Five, who lives with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, spent 2,054 days inside New York solitary confinement cells.

Ten years later, Five still suffers the consequences of that isolation .

The United Nations defines solitary confinement as “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact,” and prolonged solitary confinement as “being in excess of 15 consecutive days.” Solitary confinement is also referred to as Special Housing Units (SHU), of “the box.”

On April 1st, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo signed the HALT act, a bill to limit solitary confinement to 15 days. Though these new regulations mark a victory for criminal justice activists in New York, thousands of currently and formerly incarcerated people are still facing the consequences of the spending years in isolation.

In 2010, 12 years after his arrest, while Five was serving his 33-year-to-life sentence in his solitary confinement cell, he was exonerated for all his charges except for possession of a gun. A guard opened the door where he had isolated and gave him a one-way bus ticket to New York’s city center.

Five had not been out of his solitary confinement cell in five years, and in a matter of hours, he arrived at the 42nd Street/Port Authority Bus Terminal. This was before the pandemic when about 330,000 people would pass through Times Square daily.

He felt overwhelmed and had a panic attack. After spending the night at the hospital, he was rearrested for violating his parole and sent back to the facility to serve an additional year.

Every year, more than 10,000 people are released straight from solitary, reveals a report by NPR and the Marshall Project.

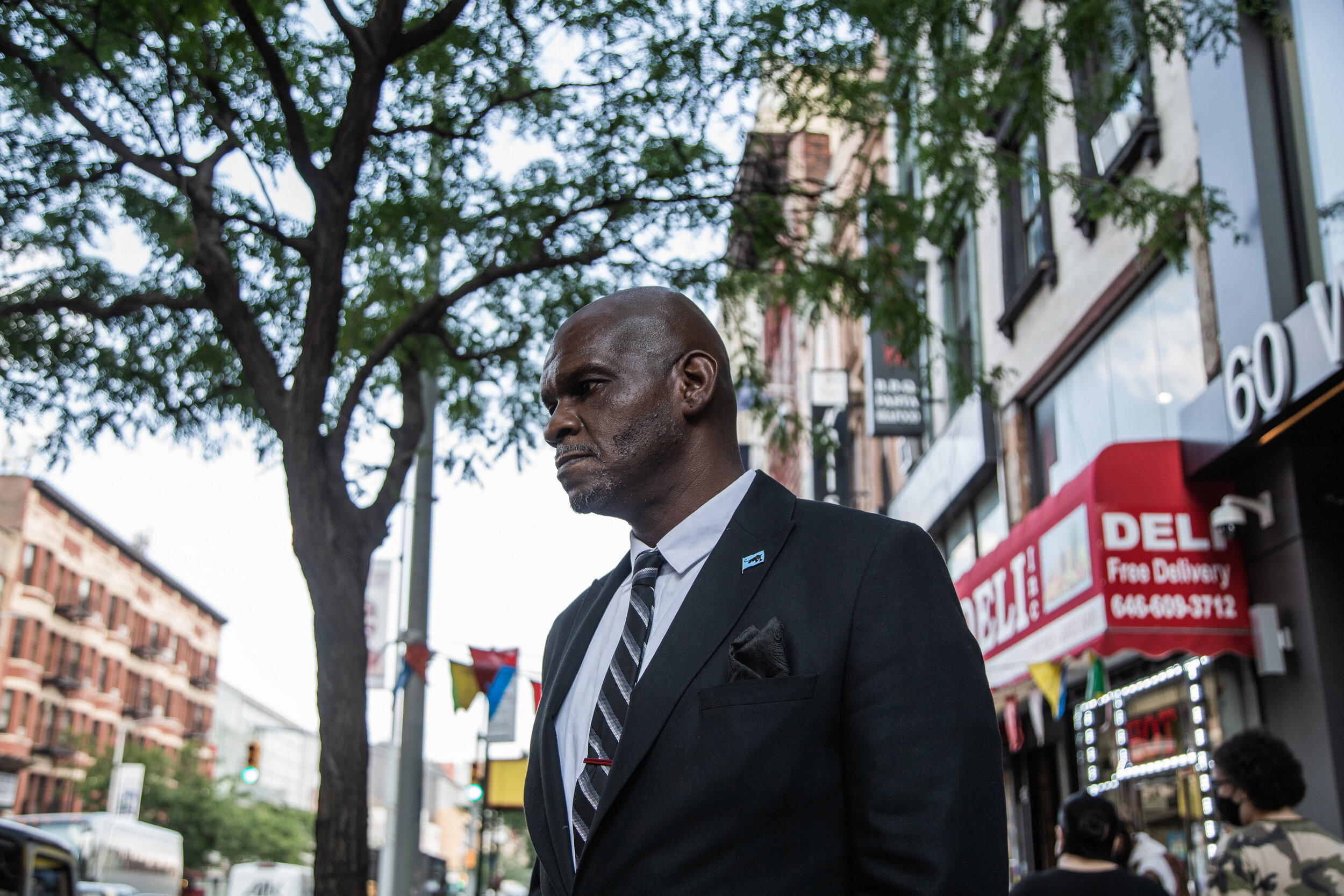

Five in The Bronx on July 26, 2021.

Kevin

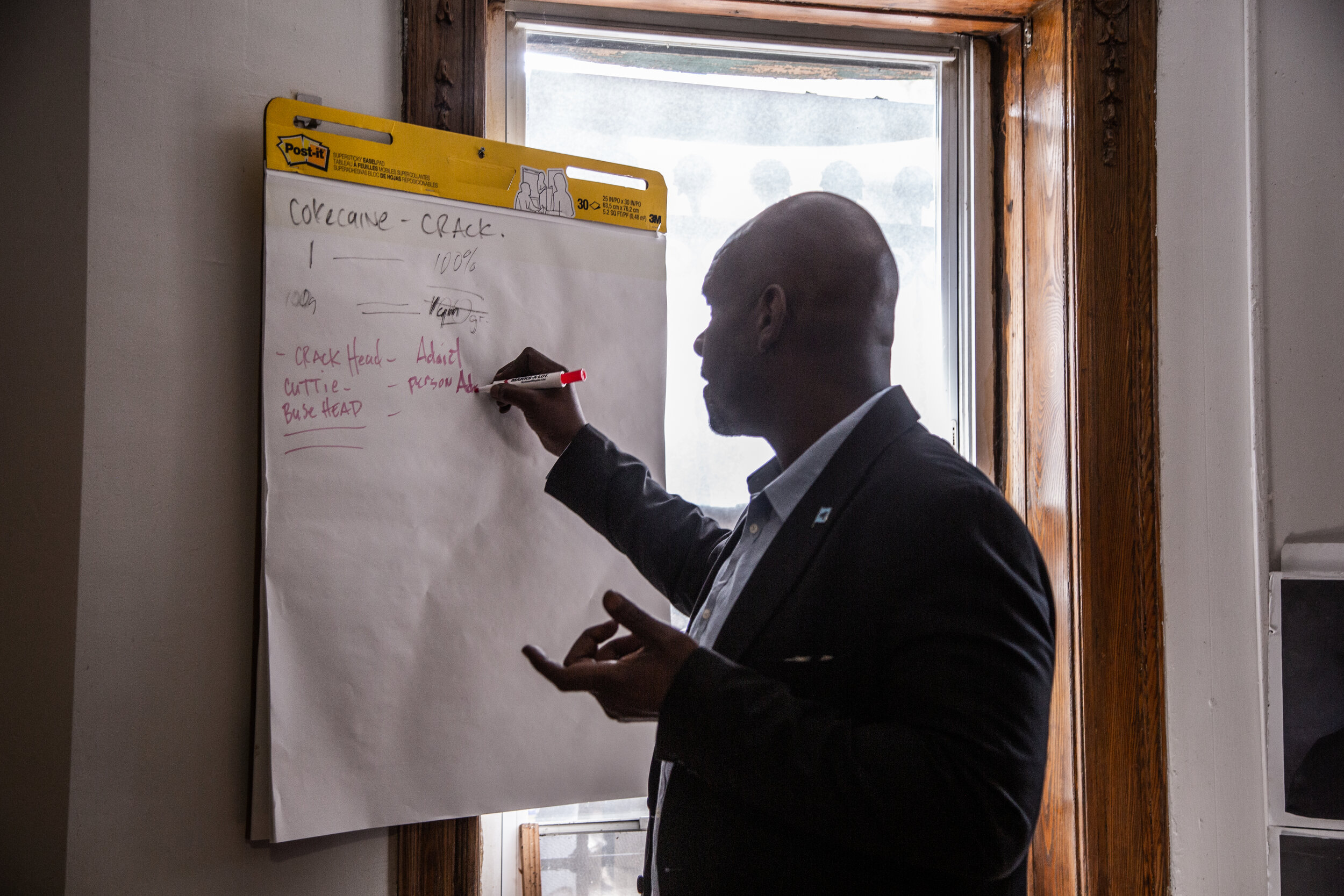

The first time Kevin Mays went to solitary confinement, he felt that he was on vacation. He knew why he was sent to solitary most of the time. “I was an agitator and an organizer. I was angry, extorting people and selling drugs,” he said. “They knew that if I was in General Population I would get in trouble.”

There are several reasons why people are placed in solitary confinement. The main one is to punish them for their behavior inside prison, most of the time for minor infractions.

But a 2016 report by the Association of State Correctional Administrators and Yale Law School reveals that the proportion of Black and Hispanic people in solitary confinement is higher than the one in the general population. In 2017, about 85 percent of people in solitary confinement were Black and Hispanic, reports the Correctional Association of New York.

Nelson Mandela Rules adopted in 2015 by the United Nations prohibit the use of prolonged or indefinite solitary confinement. But every time Mays was sent to the box, he did not know how much time he would spend inside.

Yet Mays spent 15 out of the 28 years he was incarcerated in solitary confinement. “I was very strong mentally, but sensory deprivation was still very hard,” he said. Mays went to solitary confinement a dozen times. After each time, he said, he would feel anxious being around other people.

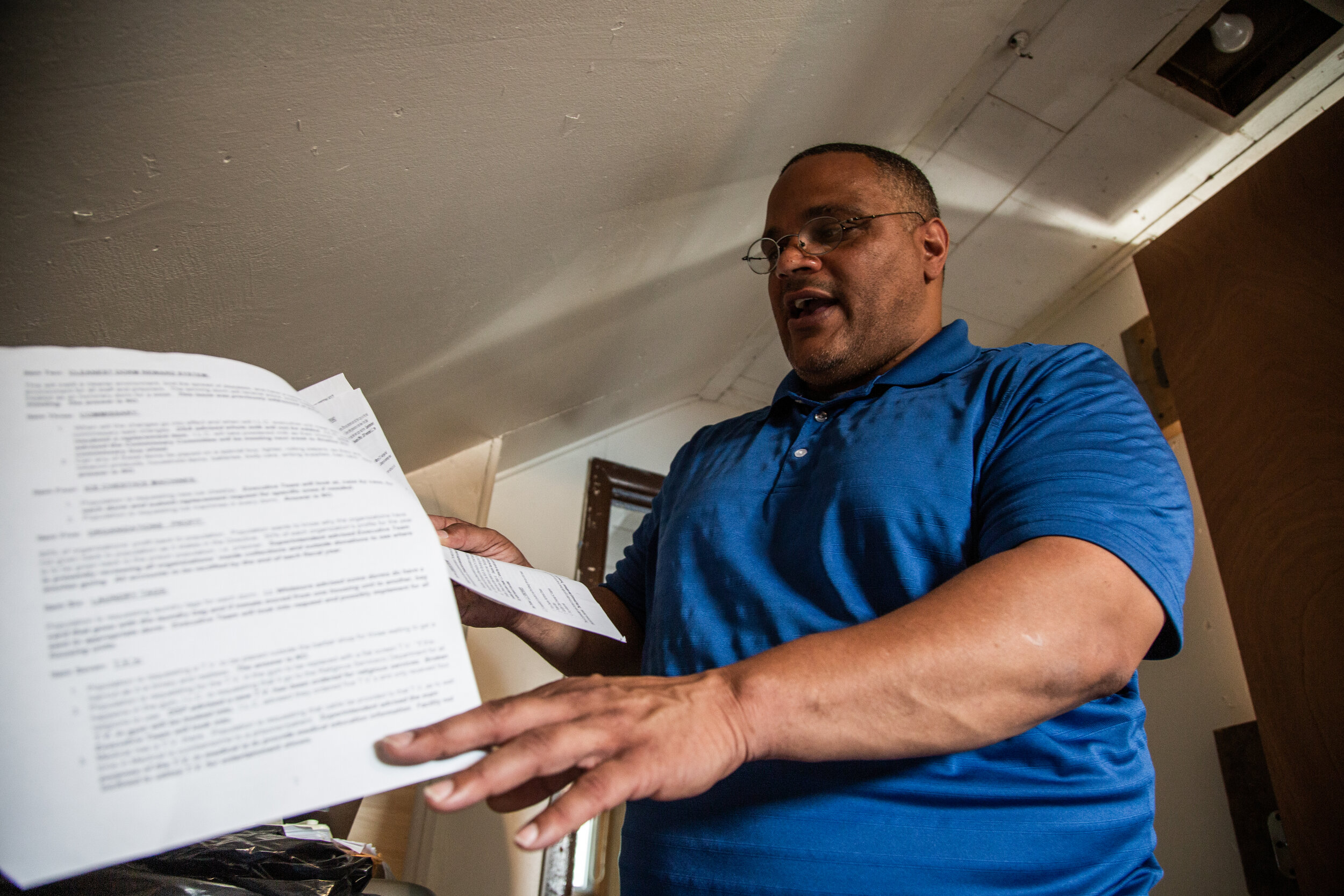

Kevin Mays reads the report that he put together from the 28 years that he spent inside New York State correctional facilities.

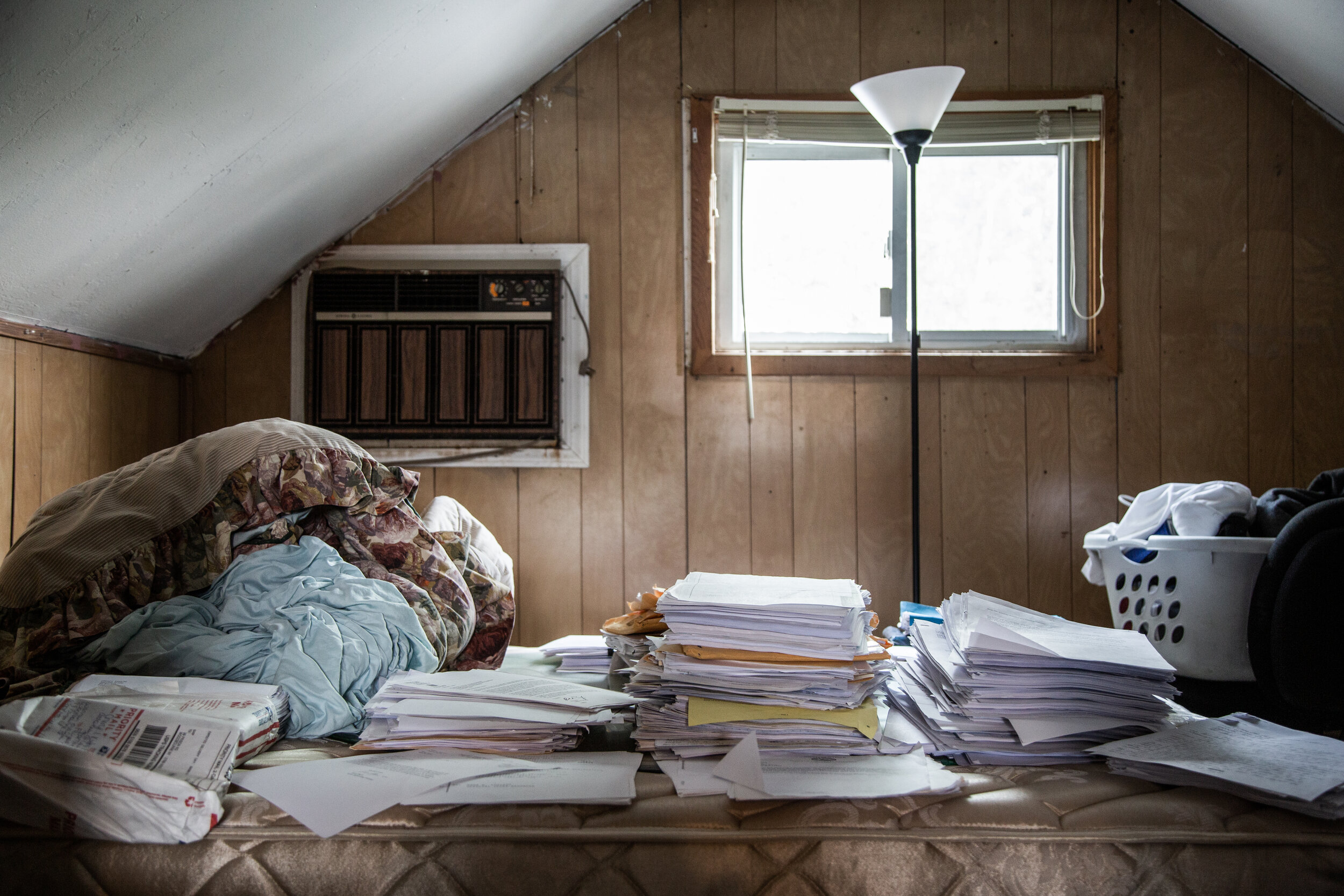

List of all the times that Kevin Mays was sent to solitary confinement. He spent a total of 15 years in the box. The longest time that he spent inside were 5 years, uninterrupted.

Kevin Mays participates in a protest to qualified immunity at Foley Square on May 21, 2021.

Darlene

Dante would spend up to $20 a day to call his mother, Darlene, several times a day. “He just wanted to talk about anything, he craved that human connection so much,” she said. “He would call me just to hear me breathe.”

But these phone calls stopped when he was placed in keeplock, a type of isolation.

Three months later, her phone finally rang. After asking for mental health counseling, which he was never provided, Dante took his own life.

“I wish I was involved before so I could have avoided it ahead of time,” she said.

After her son’s death, Darlene said that advocacy has given her a purpose. She has been investigating his death ever since, trying to bring justice to her son by fighting against solitary confinement.